Ever wonder why it feels so good to share information on Facebook or Twitter? A new study by two Harvard-based psychologists found that these status updates the same pleasure centres in the brain activated by eating a delicious meal, shopping or having sex.

Ever wonder why it feels so good to share information on Facebook or Twitter? A new study by two Harvard-based psychologists found that these status updates the same pleasure centres in the brain activated by eating a delicious meal, shopping or having sex.

Ooooh. This explains a lot.

And while posting your party pictures or tweeting your lunch choices may not hit quite the same pleasurable high notes as sexual activity (for most people), it does explain a recent survey of Internet use that show 80% of social media posts are simply announcements about one’s own immediate experience.

Part of the study involved MRI imaging of test subjects to observe brain activity as they answered questions about their’s and other’s opinions. Researchers found that the brain regions associated with reward — the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area — were very active when people were talking about themselves, and less engaged when they were talking about someone else.

In one interesting twist, the researchers also found that participants would turn down money to talk about someone else, in order to enjoy the more pleasurable sensation of talking about themselves. In the second part of the study, they set out to determine how important it was to people to have someone listening to their self-disclosure:

“We didn’t know if self-disclosure was rewarding because you get to think about yourself and thinking about yourself is rewarding, or if it is important to have an audience,” Tamir said.

As anyone with 700 Facebook friends might have guessed, the researchers found greater reward activity in the brains of people when they got to share their thoughts with a friend or family member, and less of a reward sensation when they were told their thoughts would be kept private.

What does this mean for our kids? Since we already know that the reward centre in the developing teenage brain is more active than in adults’ brains, we can see how it would be even harder for kids to control their impulses to share everything with everyone. All the time. Similar work by Laurence Steinberg at Temple University found that teenagers doing a simulated driving test took more risks — and had greatly increased activity in the reward centre of their brain — when they thought other teens were watching them.

It also makes it clearer how much harder it would be for them to exercise their still-emerging good judgement, since research on the teenage brain shows good judgement and impulse control are among the last parts of the brain to develop. As this Wall Street Journal article put it: “If you think of the teenage brain as a car, today’s adolescents acquire an accelerator a long time before they can steer and brake.”

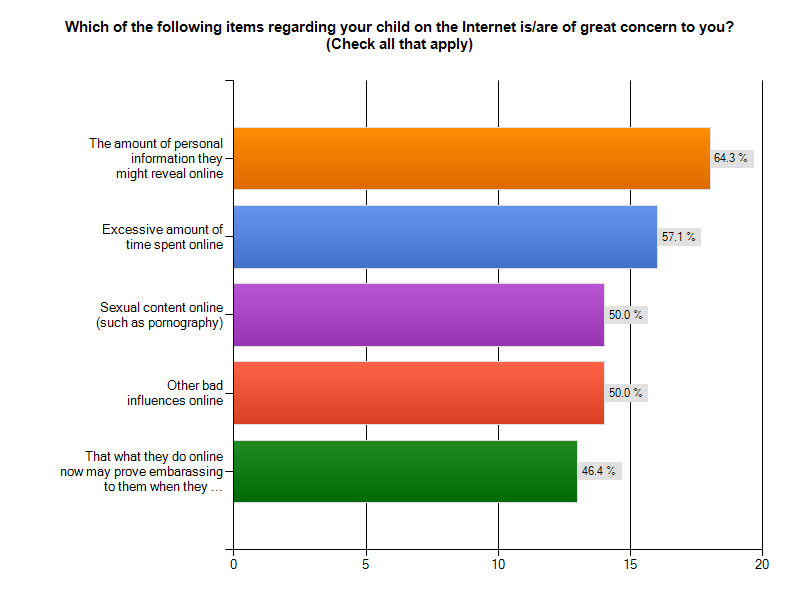

All of this means we need to work a little bit harder with our kids (and ourselves) to figure out appropriate limits on self-disclosure. Do they really need their 800 Facebook friends to know about a fight with their boyfriend, or how wasted they were over the weekend? Are they sharing details that may prove embarrassing to them next year? In 20 years? Let’s try to help them find other, safer ways to achieve the pleasure of self-disclosure, such as through actual face-to-face conversations with trusted friends or family members (I KNOW. That’s just crazy!). But knowing what’s behind it all gives us a good head start on finding workable solutions.